Published in the June 3, 2025 issue off the Raven

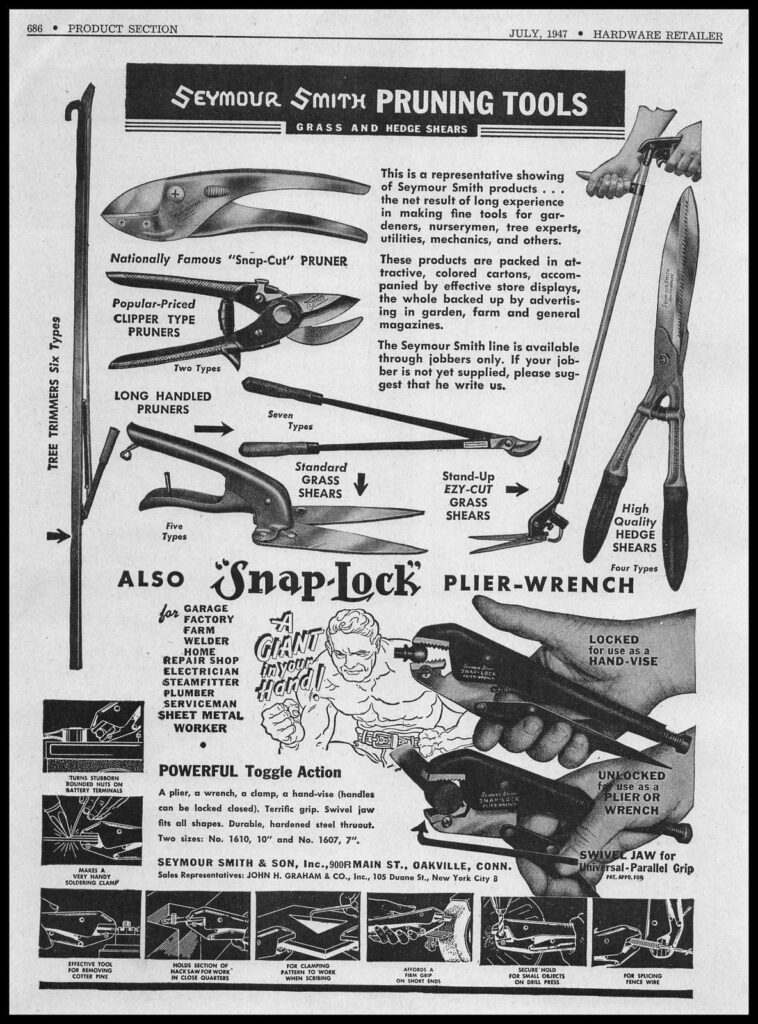

It’s hard for me to believe, but my first day of trail work was 55 years ago in Waterville Valley, volunteering with the Waterville Valley Athletic and Improvement Association (WVAIA). I worked that day alongside names mostly forgotten now but well-known in trail circles at the time: Seymour Smith of AMC swizzle stick fame; John Ensor, an AMC and WVAIA volunteer; and Paul Leavitt, who bridged the generation of older trail tenders and younger folks like me. On that day, I built my first log waterbar, instructed by Waterville’s trail masters.

While Seymour Smith’s avocation was trails, his business was tool manufacture, a multigenerational family enterprise. He was famous for inventing tools for trail work, including the “AMC Swizzle.”

A few years later, as a college student in the 1970s, I was among the first to be hired by the WVAIA to lead trail work. That same year, a young U.S. Forest Service forest technician named Dave Hyrdlika was assigned to trail duty for the Pemigewasset Ranger District. It was Dave’s first season “on the Forest.” Back then, trail work wasn’t a specialized position—“technician” was a general term for someone who did a little of everything. Dave was trained as a forester, and trails were new to him.

On our first day working together we reviewed the South Tripyramid Loop Trail with the retiring forester who had been uncharge of trails. It had serious erosion problems. I was confident I knew what the trail needed—after all, I had a handful of years working under WVAIA trail masters. I knew how to build a log waterbar, and enthusiastically proposed one after another as we walked up the long approach to the South Slide, an old logging road. Dave was more cautious, and the retiring forester simply said, “Wait. Let’s see what’s ahead.”

We walked for nearly a mile. I kept proposing waterbars. The retiring forester kept saying, “Wait.” Finally, near the base of the South Slide, we came upon a massive stormwater drainage that had once crossed the trail but was now blocked by silt and rocks, diverting water directly down the trail tread. The real problem wasn’t a lack of waterbars—it was a blocked cross-drain.

On the way back down, we did plan a few waterbars, but the key intervention was to dig out the drainage and redirect the stormwater off the trail. That became our project for the summer. We excavated a channel rather than construct the dozens of waterbars I had envisioned.

It was an unforgettable moment. My understanding of trail work was upended. I had learned one simple engineering trick and was eager to apply it everywhere. As the saying goes, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

Law of the Hammer

This “law of the hammer” reveals a common tendency in engineering and thinking: once we have a useful tool or concept, we try to apply it everywhere. We force the landscape to fit our tools, and we interpret problems through the lens of what we already know. This demonstrates both the power of accumulated knowledge—techniques that work well in the right context—and the limits of seeing the world only through preconceived solutions.

The retiring forester brought something else to the trail: a beginner’s mind. He suspended judgment. He stopped being an expert, at least for the moment. He walked, watched, and listened. Dave, with greater humility than I had at the time, took his lead.

Over the years, as I continued to lead crews in Waterville and Dave advanced into a trail specialist role with the Forest Service, we became friends and learned together. During that period I helped founded the Sandwich Range Conservation Association (SRCA), a shared trail crew crew between trail clubs in the Sandwich Range. I eventually moved to Costa Rica and raised a family. Dave retired early from the Forest Service and pursued his passion for homebrewing beer. Though trail work was no longer my vocation, it remained my avocation—as it still is today.

Becoming an Experienced Beginner

What I gained in those early years—and in the years since—is experience: I’ve seen the long-term effects of my own work. I’ve returned to trails I helped maintain and observed whether our techniques succeeded in controlling erosion. I’ve come to see trails as dynamic systems shaped by geology, soil, slope, aspect, elevation, weather, climate, and fauna—but most of all, by people. And while the foundational components of a trail remain the same, two variables have been changing rapidly: people and climate. Increased visitation and more frequent, intense rain events have accelerated erosion and introduced new environmental challenges.

Over time, I learned new techniques and adopted new tools. I came to love the rock bar and eventually mastered the grip hoist for moving large stones. Watching my wooden waterbars and soil retainers disintegrate after just a few seasons, I began favoring stone for erosion control. With this shift, the rock bar became my new hammer—once again, I had to remind myself not to treat every trail as a puzzle of stones waiting to be moved and set.

The most important and difficult lesson in trail work, I’ve come to believe, is balancing growing expertise with a beginner’s mind. I strive to be an experienced beginner.

Bricolage and the Yankee Farmer

This approach reminds me of what anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss called bricolage—a creative process in which one solves problems using whatever tools or ideas are at hand, rather than relying on specialized equipment or formal plans. The bricoleur improvises, adapting to the situation with available resources, in contrast to the engineer who follows a structured design toward a defined goal.

The stereotypical Yankee farmer is a kind of cultural cousin to the bricoleur: solving problems with ingenuity and reuse, building what’s needed from what’s nearby. It’s a mindset shaped not by abstract calculation but by practical imagination and constraint.

Law of the Pick-Mattock

In trail tending, it’s best to have at least one versatile tool. The pick-mattock—part pick that can be used for prying rock and breaking up hard-packed soil, part mattock for digging and grubbing—is one such tool. It’s not precise, but it’s adaptable. While the engineer reaches for the exact tool calibrated for a single task, the bricoleur reaches for the pick-mattock: a tool of possibility.

The pick-mattock doesn’t dictate a singular use; it invites improvisation. In contrast to the law of the hammer, which reduces all problems to one kind of solution, the law of the pick-mattock embraces the creative potential of what’s at hand—even when it’s heavy, blunt, or uneven. It’s not the tool that defines the task, but the task that reveals how the tool might serve.

Of course, there are times when we need specialized tools and precise engineering. The law of the pick-mattock doesn’t exclude the use of hammers, rock bars, grip hoists—or even rock drills. It’s always a matter of balance: knowing when to improvise, when to standardize, and when to observe before acting. I would argue that the best engineers develop the quality of being experienced beginners.

Looking Ahead

White Mountain trails are in crisis. Use is rising, storms are harsher, and the public systems once tasked with caring for trails are themselves eroding—funding cut, staff reduced. Increasingly, work is carried out by nonprofits and volunteers, piecing together financial and volunteer resources as they can. In this shifting landscape, we need not just plans and precision, but improvisation. We need more bricoleurs—more Yankee farmers—making do with what’s at hand, guided by care, memory, and ingenuity.