“To begin with oneself, but not to end with oneself; to start from oneself, but not to aim at oneself; to comprehend oneself, but not to be preoccupied with oneself.”

— Martin Buber

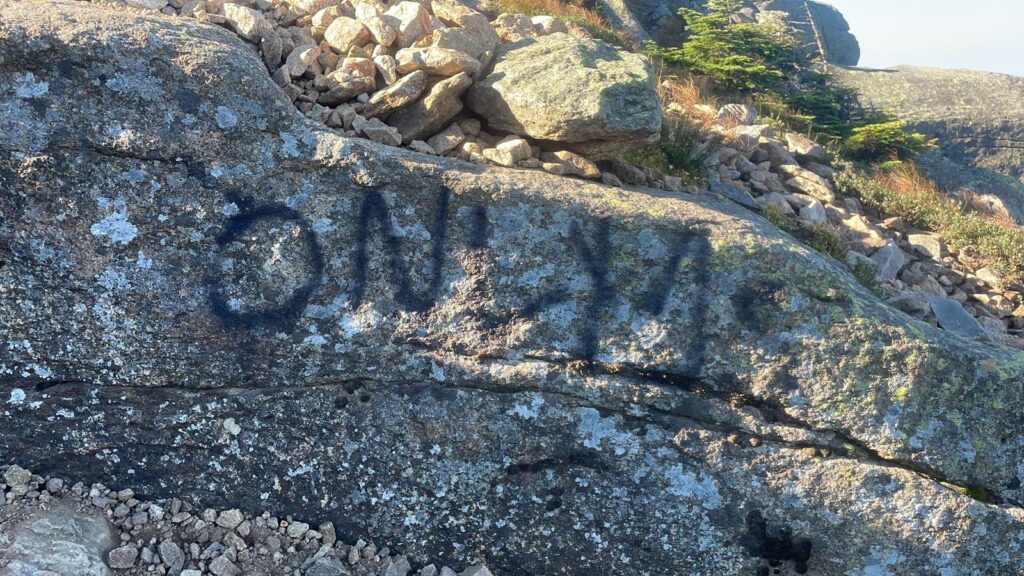

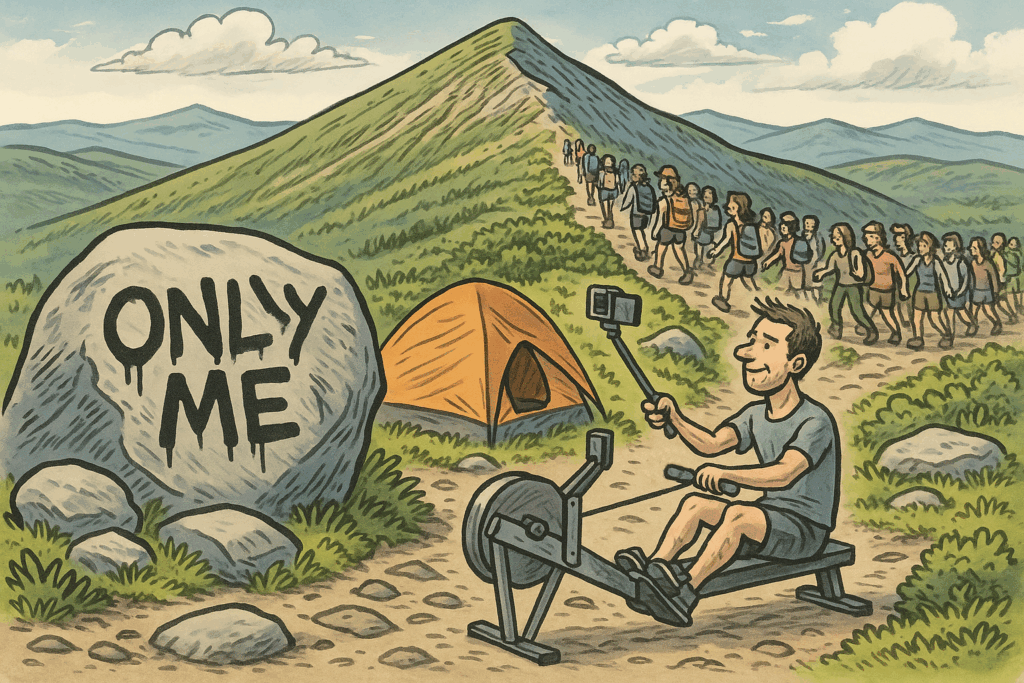

Jess and Demi’s reports and photos from last weekend on Franconia Ridge left me disheartened. Graffiti on rocks and ledges, an abandoned tent in the alpine zone, the usual overcrowded summits—and then, astonishingly, someone who had hauled a rowing machine to the ridge. Taken together, these images left me stunned. I try to recognize that people experience and enjoy the outdoors in different ways—often very different from what I would choose. But the risk in sliding too far into relativism is that we lose our ethical grounding.

Aldo Leopold offers one of the simplest and most direct definitions of ethics:

“All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts. His instincts prompt him to compete for his place in that community, but his ethics prompt him also to cooperate…”

In one of the graffiti scrawls I saw the words “Only me.” Whether that was what the author intended to write, it seemed fitting: a declaration of narcissism. In a world of “only me,” there is no community, no sense of responsibility, no ethics.

Leopold believed ethics can and must expand beyond human-to-human relations: “The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”

To stand on Franconia Ridge is to recognize and respect not just the thousands of fellow hikers, but also the alpine plants, the ravens and other wildlife, the thin, fragile soils, the brooks and streams rushing down into the Pemigewasset Wilderness. All are part of our community.

Trophies

Leopold also spoke of a conservation “esthetic,” the idea that recreation in nature could cultivate deeper values. He discussed how seeking “trophies” can connect people to the land. He distinguished between direct and indirect trophies.

A direct trophy is something extracted from the land—antlers, a trout, a pressed flower. This can be sustainable when taken sparingly, but they consume what they commemorate. By contrast, an indirect trophy—a photograph, a field sketch, a journal entry—leaves the land intact. For Leopold, indirect trophies marked a step toward ethical maturity: they satisfied the desire for memory while protecting the resource.

But on Franconia Ridge today, indirect trophies are no longer harmless. The summit selfie, once a private snapshot, has become a mass ritual. The “4000 Footer” list turns a personal memory into a public badge, fueling competition and overrunning some fragile summits just because they have surpassed an elevational threshold. Social media magnifies the effect: a single TikTok or YouTube of someone rowing on Franconia Ridge or posing in an alpine meadow can summon hundreds of imitators. The land is not consumed by the photo itself, but by the trampling, crowding, and performance required to produce it.

From I–It to I–Thou

Direct or indirect, trophies reduce nature to an object that we stand apart from, connected only in a utilitarian way. We press the flower, post the photo—each becomes something we possess rather than a relationship we enter into. This is what the philosopher Martin Buber warned against in his description of the I–It relationship, where others we encounter in the world—whether part of the natural world or people—are reduced to objects for our use.

A land ethic, by contrast, draws us into what Buber called the I–Thou relationship—an encounter rooted in reciprocity and respect, where soils, waters, plants, and animals are not “its” but fellow members of a shared community. Here the flower is left to bloom, the photograph held as a reminder rather than a badge. The experience is not about possession, but about participation in a living whole.

We

Leopold hoped that indirect trophies might nurture a conservation ethic, cultivating appreciation that deepens our connection to land. For us, the task is to rediscover that possibility in a digital era where images multiply endlessly and summit challenges have become part of our outdoor culture. Could the 4000-footer traditions—in all their variations, from winter ascents to the Direttissima—be embraced not only as personal achievements, but also as pathways to deeper care for the mountains themselves? Could photos be gestures of reverence as much as a celebration of achievement? Could our stories and records highlight the alpine community that makes these places so meaningful?

Sometimes the most ethical choice lies not in what we do, but in what we refrain from doing. Restraining the impulse to claim a trophy—whether it is a photograph, a peak, or a list completed—can be a gesture of respect when we recognize that our action might cause harm. At times, deciding not to climb or run an already overburdened summit may be the wisest course. In the same way, choosing not to post a photo or video on social media—resisting the pull of performance—can itself be an ethical act, a gesture of humility toward both the land and our human community.

The graffiti on Franconia Ridge reminds us of what is at stake. To move from “Only me” to “we” is to recognize that Franconia Ridge is not a stage for performance, but a living community—one to which we belong, and for which we share responsibility.

Selected Bibliography

Leopold, Aldo.

- A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. Oxford University Press, 1949.

—Seminal collection of essays in which Leopold articulates his concept of a “land ethic,” calling for a responsible relationship between people and the land they inhabit.

Buber, Martin.

- I and Thou. Translated by Walter Kaufmann, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970. Originally published as Ich und Du, 1923.

—Foundational philosophical work exploring the nature of relationships, particularly the contrast between “I–It” (objectifying) and “I–Thou” (relational) modes of being.

Additional Resources

- Flader, Susan L. Thinking Like a Mountain: Aldo Leopold and the Evolution of an Ecological Attitude toward Deer, Wolves, and Forests. University of Wisconsin Press, 1994.

- Friedman, Maurice S. Martin Buber: The Life of Dialogue. University of Chicago Press, 2002.