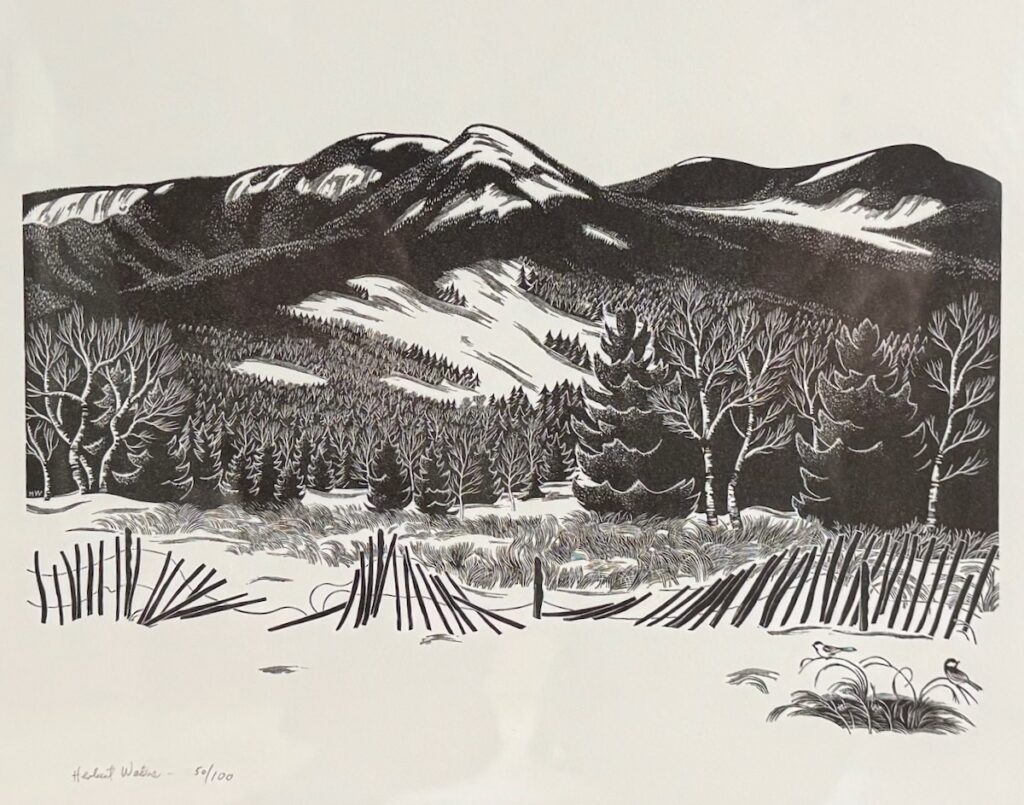

As we complete the fourth year of the Partnership to Restore Franconia Ridge (third year for Pan American Trails/WTN Americas), it is increasingly clear that the existing federal funds will not support significant improvements to the Franconia Ridge Trail itself. 1 The $1.125 million in federal money secured through the AMC with the help of Senator Shaheen will soon run out, and the private funds Pan American Trails/WTN Americas has raised are directed toward the Old Bridle Path and Falling Waters Trail in Franconia Notch State Park—below the alpine zone.

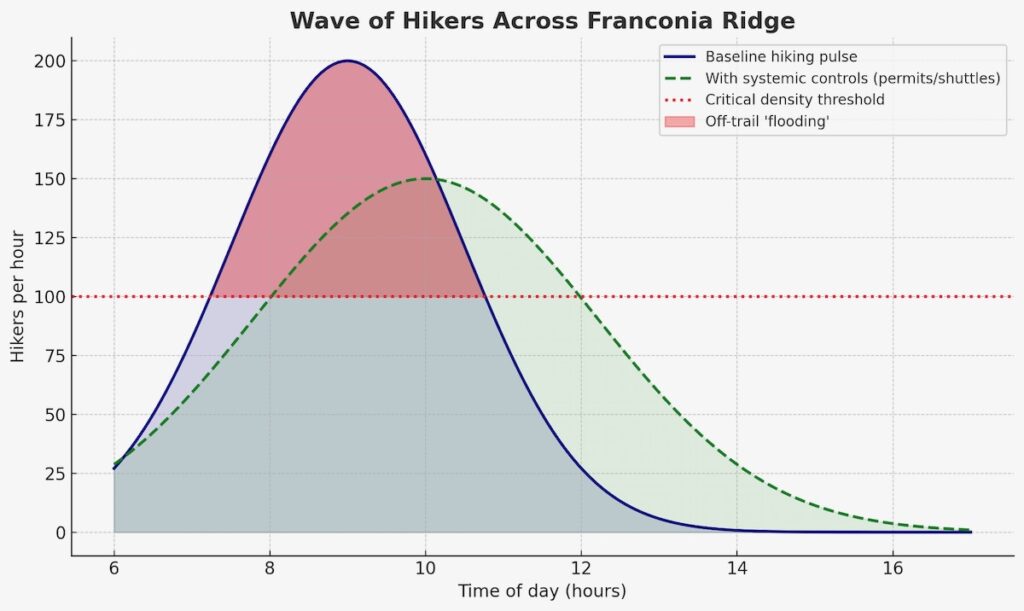

This project was named for Franconia Ridge and justified in part as a way to protect its fragile alpine area. Yet by improving the two main access trails, we risk funneling even more people into the alpine zone. Unless the USFS and Franconia Notch State Park take action to limit use, or we redesign the Ridge trail to accommodate current numbers, the alpine zone will deteriorate further.

A Trail Exceeding Capacity

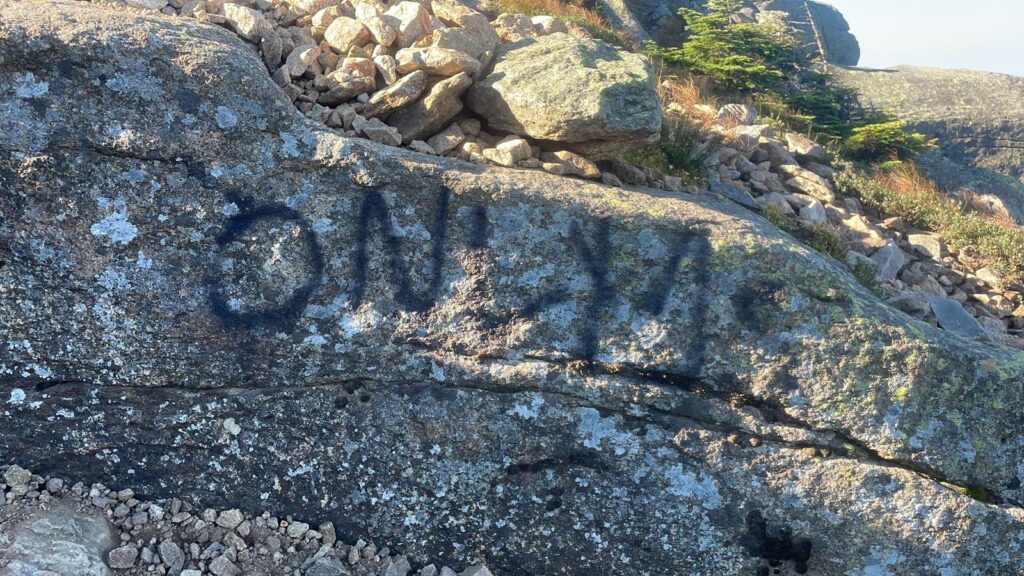

The research and monitoring of Pan American Trails/WTN Americas Summit Stewards, students, and Trails Fellows show what many of us witness every weekend: Franconia Ridge is often well beyond capacity. Without the presence of stewards on the Ridge—both Pan American Trails/WTN Americas’ professionals and AMC’s volunteers—the alpine zone would be even more deteriorated. It is constant work—maintaining scree walls, piling brush and rubbling trampled areas, adding string fencing—that keeps most visitors on the trail. Thanks to this stewardship, we now see stabilized soils and revegetation in some areas.

Even if new policies reduced visitation by a third, the Ridge would still require weekly tending and a permanent steward presence.

What the Franconia Ridge Needs

We do need thoughtful tread reconstruction on Franconia Ridge, but it must be carefully tailored to the Ridge’s geology, ecology, and visitor behavior. The first step is a detailed inventory of places where off-trail behavior consistently occurs: narrow pinch points, sections with high rugosity (protruding rocks in the tread), high steps, steep grades, and unclear boundaries.

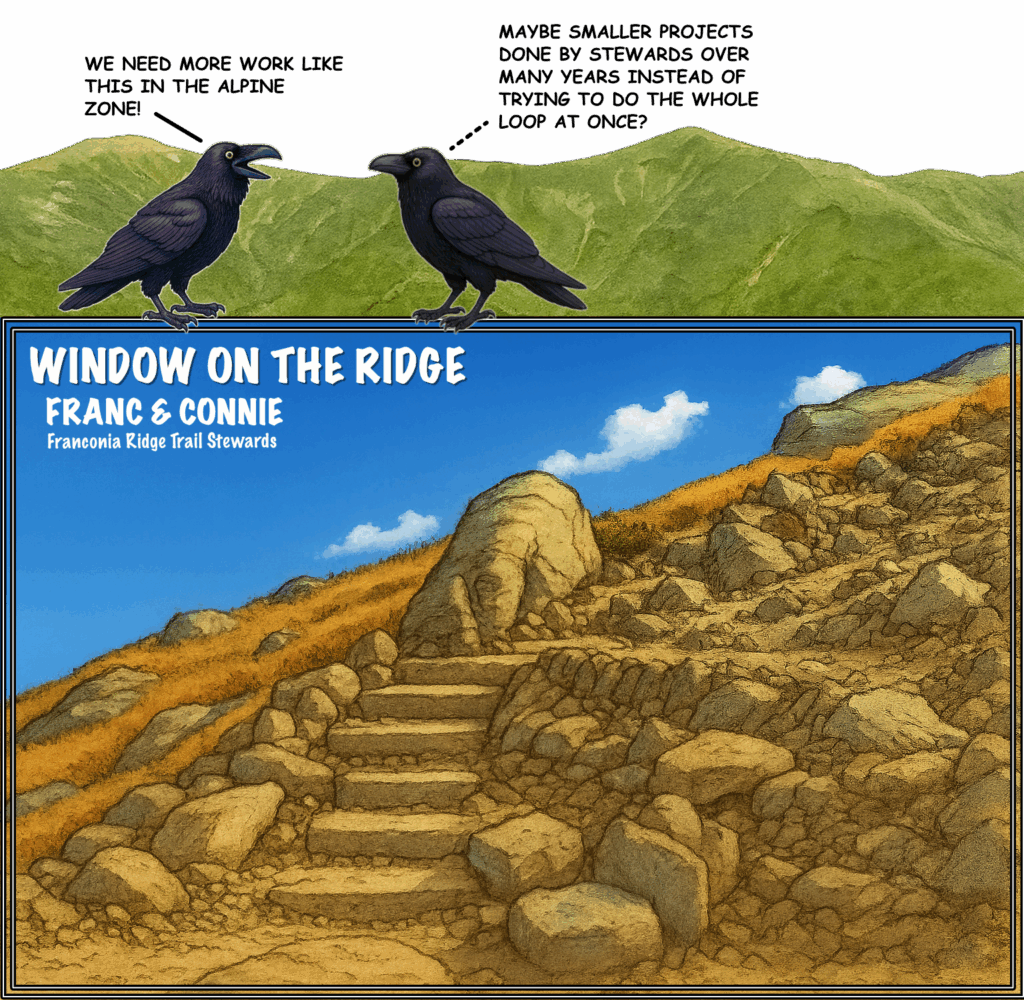

From there, we can apply our recognized toolbox of solutions—widening the trail, adding pullouts, removing obstacles in the tread, rebuilding steps, short relocations, rebuilding scree walls, and installing string fencing. This should happen over time, not all at once.

Who should do this work? Small alpine-experienced crews—two or three people who understand how hikers move through this terrain. Their work could proceed slowly, section by section, integrated with ongoing maintenance and adjusted as they see what succeeds and what fails. In this way, a consistent annual program of trail repair becomes part of the fabric of stewardship—like the Golden Gate Bridge, which is painted continuously, this work never finishes.

Even the best-built drystone scree walls on Franconia Ridge begin to fall apart almost immediately when knocked by hikers and runners. High-quality rock steps shift and become undermined in just a few years, succumbing to gravity and the impact of 45,000 visitors a season. Trail work must be revisited, repaired, and sometimes redesigned and adapted to new patterns of use.

Summit Stewards are uniquely positioned to play this role. They already devote less busy days to trail work. With additional training, stewards could tackle more technical projects, like rebuilding rock steps.

And of course, there is string fencing to replace, waterbars to clean, and signage to refresh. Stewards currently complement trail work with indirect management: providing information, education, and interpretation to visitors; conducting environmental and social monitoring; leading volunteers; and working closely with AMC Alpine Stewards and USFS Trailhead Stewards. All of this is coordinated with and overseen by the USFS. Trail-based management is further complemented by administrative policies such as potential visitor use limits, group-size limits, and parking/shuttle management in Franconia Notch State Park.

Taken together, this is integrated trail management: trail tending.

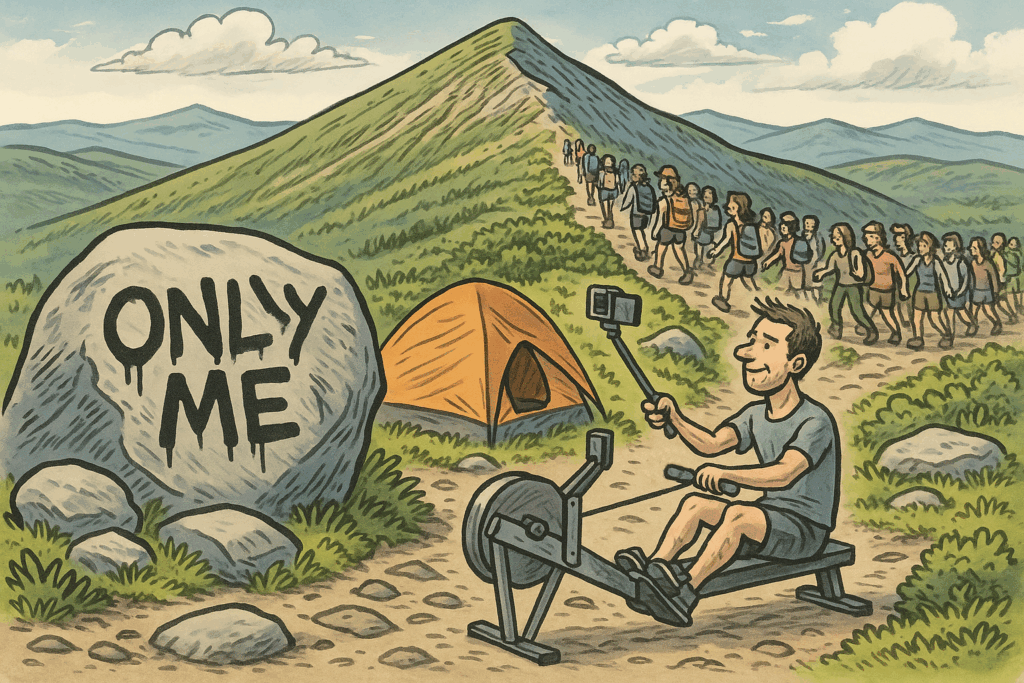

The Limits of “Big Project, Big Funding”

This vision stands in contrast to the recent model of massive, multi-crew projects focused only on trail reconstruction. The Crawford Path project and the current Franconia Ridge partnership exemplify this “big project, big funding” approach. While it may sustain large trail departments, the results are mixed: work quality varies, and when the money runs out, crews disappear—finished or not. Worse, it feeds what I call the engineer’s conceit: the idea that if you just build a trail “right,” the job is done.

Good engineering and design do matter—Inca stonework in South America has endured for a thousand years, a testament to what careful construction can achieve. But no trail, however well built, is ever truly “finished.” Every trail requires constant revisiting, with regular maintenance, and adjustment and adaptation over time as climate and use patterns change. One reason so many White Mountain trails are in poor condition is that trail maintenance has been segregated from trail construction and reconstruction and treated as second-class work, rather than as the heart of stewardship.

The Role of Summit Stewards

Nearly five years ago, when “restoration” funds for the Franconia Ridge Loop first appeared, the Summit Steward program was excluded from sharing in the grant—because at the time the USFS and AMC did not consider stewardship “tread work.” I believed then, and still believe now, that this was a mistake. Over the four years of the partnership, it is Summit Stewards and volunteers who have in fact done the only tread work on the Franconia Ridge Trail itself.

Thankfully, the USFS has come to recognize this and has increased its funding for the Summit Steward program. The Waterman Fund has been a consistent supporter. Even so, it remains a struggle to find enough funds to keep Summit Stewards on Franconia Ridge every year.

Looking Forward

As the Partnership to Restore Franconia Ridge Loop winds down, we should not be chasing ever-larger grants to stage logistically complex projects that vanish when the money dries up. Instead, let’s invest in a dedicated cohort of specially trained Summit Stewards—small, skilled teams who can continually rebuild, adapt, and maintain the Franconia Ridge Trail.

The alpine zone demands nothing less.

- The Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) professional crew did some excellent work building scree wall and and cairns on the summit of Lafayette and on the upper Greenleaf Trail, and recently an AMC led Vermont Youth Conservation Corp crew did equally high-quality work on the upper Greenleaf Trail. But no work has gone beyond the summit of Lafayette on the Franconia Ridge itself. ↩︎